Why Observables, not just Promises?

Objective: Understand how top-notch UX featuring cancelation and incremental progress, can only be achieved with Observables, which - unlike Promises - reach parity with UNIX processes.

The Promise, as a datatype, is not a complete solution for async. A Promise does not offer cancelation, which you need to prevent resource leaks or race conditions. And a Promise only delivers its single value at the end - meaning you can't get progress notifications, or incremental delivery. Promises are a kind of async data type that are useful for a common, simple case of async. But imagine we had a data type that handled all async use cases! It's not hard to do - let's start from first principles!

Theory

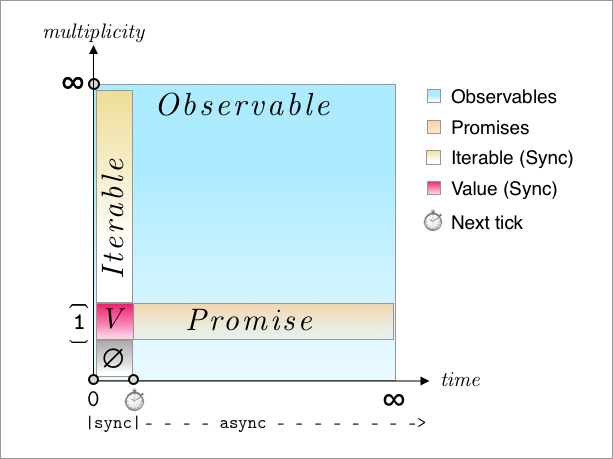

This graph will succinctly say what the rest of this post will elaborate: Promises, singular values, they are all specializations of Observables. Promises only can hold future values - not present ones. Observables can hold either. Promises can't be canceled. Observables are always cancelable (but could have a no-op cancelation function). So if you regularly mix synchronous and asynchronous data, as in most web apps, composing with Observables will result in generally cleaner code than with Promises. You treat data the same whether it arrives singly or multiply, and whether it exists in the present (sync) or the future (async).

The point of this article is that we have painted ourselves into a corner by using Promises, and can get out of that predicament by using Observables to represent the return value(s) of single- or multiple- value processes.

Until the rise of AJAX, the main objects you could refer to in JavaScript were synchronous. Numbers, booleans, strings, objects, arrays, functions, and combinations thereof are all synchronous data types. In the graph above, they are the left-most slice of the chart. Every value - be it a null/undefined, a single value, or an iterable Array-style value was fully usable with while loops, if statements, etc..

With the rise of AJAX, an inherently asynchronous technology, because there wasn't an object yet for a future value, an "asynchronous value", callback hell ensued. Then—coders decide to extend the notion of a value by defining a Promise - a future value. On the graph above, it is the region to the right of the single synchronous value. This magical future-value - when prefaced with the word await - can produce a synchronous value! But there's a real problem now - Promised values and synchronous values just can't compose!

As Bob Nystrom points out in What Color is Your Function?, you can only call await inside of an async function - so if you can't change your function to an async one, you can't handle that async value. The problem is that the return value from one function - a Promise - cannot be combined with the return value from another function - say, the current sales tax rate in all situtations.

This is the reason we need a single datatype that can be single- or multi- valued, and over any amount of time. Something that in the graph above, spans the whole plane. If every function that encountered async returned one of these - an Observable - then any app that was set up to consume Observables could seamlessly transition from sync to async - from single- to multi- value, and there wouldn't be the challenge of async tainting an entire call stack of functions.

Now, let's see a concrete case now that a Promise cannot model - that of a UNIX process. I think it needs no proof that the abstraction of a UNIX process has not been found lacking in any fundamental way in 50 years. So let's see what it would take to extend a Promise to actually model a UNIX process!

A UNIX Process in JS?

Imagine trying to control a UNIX process with a Promise! You couldn't cancel it - and if delivered lines of output over time, you could only return them to the user all at the end. So clearly Promises do not generalize well. What are Promises lacking? Multi-value, and cancelation - so let's build them in.

Multi-valued

In a Promise constructor, the process can only call resolve(value) once, or reject(error) once. This is what prevents it from communicating multiple values or progress increments.

So lets begin by expanding that API to allow for multiple values to be delivered - by turning resolve() into next(), and separating from complete() and error():

So - 3 callbacks, to Promise's 2. Since a UNIX process' successful completion value is zero, our MultiType's complete event will accept no value, only its error event will. MultiType will notify of values through its next event, like a UNIX process delivers lines of output. A MultiType for a timer might look like:

Lazy and Unicast

Now, for reasons we won't explain right now, we want this MultiType to be able to spawn the process that generates values, not to represent the values themselves.. We want to ensure that this data type is lazy.

A MultiType instance is like the string

ls -l- it represents the only the ability to spawn a process.

So let's imagine MultiType to be a "Process Spawner". And you will cause it to spawn a process by calling .spawn():

Now you see how the ticker MultiType represents the capability for a series of notifications, but the Process is the result of spawning it.

Now that we understand our MultiType/ProcessSpawner - let's reveal its true name - Observable, and its cohortsObserver and Subscription :)

Here you see the number ticker, with the correct type names.

To summarize: with Observables, to spawn a process, you call .subscribe() on an Observable, optionally passing in an Observer to handle its lifecycle events. The object returned from subscribe() is a Subscription — which represents the running process — and you can cancel the Process by calling unsubscribe().

Cancelation

How do we implement cancelation in our Observable? Well in our example, we set up an interval - so how do we arrange it so that clearInterval(id) is called when the holder of a Subscription calls unsubscribe()? How about we return it in a cancelation function?

By returning the cancelation function right when we construct the Observable, we ensure that the clearInterval code will be run when the Subcription holder calls .unsubscribe().

With that we can do everything a UNIX process can, and so we have a complete Async data type!

Summary

This table summarizes the main API and behavior characteristics of both Promises and Observables:

represents

A future value on its way to resolving

Potential for a value-producing process

callbacks

resolve, reject

next, complete, error

cancelability

AbortController

Subscription

eagerness

eager

lazy

values

1

0 - ∞

timing

only async

sync, async

On to RxFx

Now, this is all well and good, but Observable breaks the assumptions that make working with Promises so easy - you can't just call await and have it work! Plus you have those messy Subscriptions laying around in addition to the Observables.

Thankfully, if we add another layer around Observables, we can hardly ever see Subscriptions, and we won't miss await. This is where RxFx comes in.

Last updated